By Bob Hulteen

By Bob Hulteen

When you hang around a lot of Lutheran Christian-types (and their ecumenical friends and allies), you often hear the phrase “spiritual discipline” as a necessary part of following the way of Jesus. The more you poke at what is meant, the more complexity you recognize around not just the phrase, but its life-changing perspective.

For monastic leaders over many centuries of the Christian movement, “discipline” meant commitment to prayer, to poverty, to the stability of community. For Saint Ignatius Loyola, these disciplines were deemed “spiritual exercises.” Franciscans often called disciplines like fasting their “spiritual ideals.”

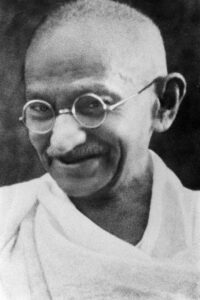

This photograph of Mohatma Gandhi is in the public domain.

To the Rev. Dr. James Lawson, who died a month ago today, it also meant confronting the “powers and principalities” that made both the sacred and the profane areas of life more challenging for the most marginalized. After spending a year as a Methodist missionary in India, studying the teachings of Mohatma Gandhi, he dedicated his life to nonviolent, direct action models of change.

“For Lawson, Christian faith demands the kind of discipleship required to truly engage Gandhi’s suppositions.”

After coming home from India and spending a year in jail for draft resistance during the Korean War, Lawson entered the Graduate School of Theology at Oberlin College. It was there that a visiting lecturer, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1956 agitated Lawson to join his freedom movement by bringing his nonviolent resistance perspective and training to the South.

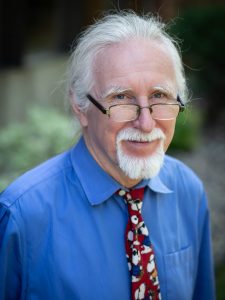

This photograph of James Lawson is available under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Lawson was a critical part of the success of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s. Confronting the sinful Jim Crow laws that dominated the era, he led famous sit ins at lunch counters and marches for freedom.

IT’S RIGHT AND GOOD to remember Lawson for the hero he has been. During these days, it is a critical spiritual exercise to remember his church-based nonviolent training of the movement. He was perpetually preparing church members and college students for what was inevitable for those working for social change.

These days, with heightened polarization around crucial social and political issues, I am thinking of his interaction with Gandhi’s perspective. While at Sojourners I was introduced to Gandhi’s “Seven Deadly Sins.” (We even sold it as a poster through the magazine.) Below are the planks of Gandhi’s thoughts about the dangers of the temptations we all must face; I share them for your consideration.

- Wealth without work

- Pleasure without conscience

- Knowledge without character

- Commerce without morality

- Science without humanity

- Religion without sacrifice

- Politics without principle

For Lawson, Christian faith demands the kind of discipleship required to truly engage Gandhi’s suppositions. Jesus’ words call us to the cross. Lawson’s biographer, David Halberstam, wrote of Lawson, “[H]e was a true radical Christian who feared neither prison nor death.” But, he was always prepared for either if that was part of being a follower of Jesus.

This photograph of Dietrich Bonhoeffer is made available by the German Federal Archive (Deutsches Bundesarchiv.

He was not unaware of what the cost for social change would be. Lawson was the person who encouraged King to lead the march for sanitation workers in Memphis in 1968, during which King was killed. He bore great guilt over his invitation.

“Bonhoeffer’s commitment to an “uncompromising discipleship” rooted in the Sermon on the Mount ensured that he would run afoul of the Nazi regime.”

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, after his life-altering years living and worshiping in Harlem, also knew of the need for discipline to face the trials of our times. Referring to the need for a new monasticism, he believed that the Sermon on the Mount detailed the disciplines of the faith.

Bonhoeffer’s commitment to an “uncompromising discipleship” rooted in the Sermon on the Mount ensured that he would run afoul of the Nazi regime; his death the inevitable result of his spiritual practice.

We are called to be disciples, clearly. As disciples, we learn the disciplines of our faith. And, we – each one of us – must ask what we are doing intentionally to put feet to our thoughts. We do so not for God’s sake, but for the sake of those that Jesus charged us to love – our neighbors.