By Bob Hulteen

By Bob Hulteen

Do you remember the first piece of art that so moved you that you couldn’t stop thinking about it for days? Do you know why you were so affected?

I remember my first encounter with “The Census at Bethlehem” by Flemish Renaissance artist Pieter Brueghel the Elder in my art history class at Concordia College. Now, this class met early every other morning (seemingly 5:00 a.m., if my memory is correct) and it’s surprising I recall anything. But one morning I was stunned by a particular painting mentioned by my professor.

“The Census at Bethlehem,” by Pieter Bruegel the Elder – Web Gallery of Art: Image Info about artwork, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15451995

I was first attracted by its religious title, alluding to Jesus’ birth but with a winter scene I recognized. (I mean, from my limited experience, if Jesus was born on December 25, shouldn’t there be snow?) I loved the grays and browns, the subtleties of color and shape.

“The biblical story of the birth of Jesus had never meant so much to me.”

And then I saw Mary on a donkey led by Joseph, heading toward an inn. Of course, I knew intimately the biblical story; but, it had never meant so much to me. For the first time – I hate to admit I was 20 and it was the first time – I realized that the biblical stories involved real human beings, not just props for God’s use.

In Bruegel’s offering, children are having a snowball fight. A pig is being slaughtered. A beggar sets a bowl out, hoping for life-sustaining contributions. Workers load branches onto a wagon. Travelers carefully cross the frozen river, carrying heavy loads. And among these “common people” was the Holy Family.

The pregnant Mary was real. Joseph was real. The inn keeper had a life outside of providing hospitality. The donkey had probably carried many people over many miles, fueled by hay grown by peasants (who are represented well in other Bruegel paintings).

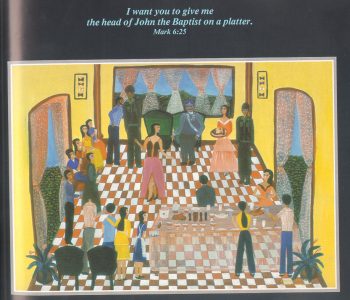

I EXPERIENCED THE same excitement when I first saw the cover artwork of The Gospel of Solentiname, a commentary on the gospels by Father Ernesto Cardenal. He tells the story of the base Christian community movement in Nicaragua during a desperate, violent time.

What most caught my attention was the fact that these mostly illiterate peasants learning to read scripture with such passion that they could see themselves, their families, their work, and their ministry in the different stories, parables, and poems of sacred scripture. These laypeople could identify with many of the subjects Jesus talked about – day laborers, evicted small landowners who now were tenant farmers, those not invited to wedding feasts.

An internal page of a storybook excerpt of “The Gospel of Solentiname”

These lay theologians were encouraged by Jesus interest in their very “beingness.” And others like them flocked to this new reading of the gospel.

“This Jesus we worship loves real, complicated people.”

I have wondered if German peasants flocked to Martin Luther’s movement as the scripture was made plain to them in their own language for the first time. Did the expansion of Lutheranism across Northern Europe interact with movements of empowerment of the dispossessed?

The art of peasants of Solentiname and the paintings of Pieter Bruegel make me think so.

This Jesus we worship loves real, complicated people. People who pay taxes and participate in census-gathering, people who travel long distances for the protection of their children, people who grow grain to feed donkeys or to feed the world, people who shovel snow and have snowball fights with their children.

Our God doesn’t love abstract people or love them abstractly. God accepts and loves real people with real, messy, complicated lives. For that, I am truly grateful.

Postscript: I was able to see “The Census at Bethlehem” at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Brussels, Belguim, in 2013. It did not disappoint.