By Brenda Blackhawk

By Brenda Blackhawk

My great-great grandmother was born in 1896 in a wigwam in Nebraska. She died peacefully in her sleep in 1999, at the age of 103. I was 11 years-old when she passed. I never got spend much time with Minnie Gray Wolf Littlebear, but the times I did made an impression.

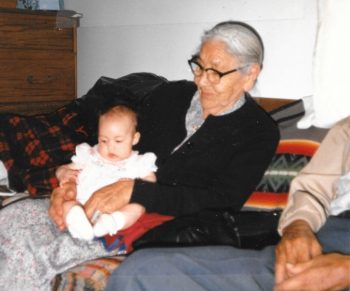

I only ever recall her being in a wheelchair, but everyone says she was tall. From the eyes of a child, she was ancient – wrinkled brown skin, hunched shoulders, white hair, and thick glasses. She preferred skirts and dresses to pants, always had a smile for her grandchildren, and had a major sweet tooth. Though she lived to an exceptional age, she never suffered the loss of her mental faculties.

“My Gaga Minnie still knew and practiced many of the old traditions of our people and was a wealth of knowledge when so much had been lost.”

She was revered by her family and tribal nation. She still knew and practiced many of the old traditions of our people and was a wealth of knowledge when so much had been lost. She gave me and most of her other grandchildren their Winnebago/Ho-Chunk names. The tribe threw her a huge birthday party when she turned 100 and people came from all over to appreciate her.

One thing I remember about Gaga (grandmother) Minnie was that I never heard her speak English. When we would visit her, my Choka (grandfather) or Jagi (father) would translate. It wasn’t until I was much older that I learned about Indian Boarding Schools – and that Gaga Minnie attended one.

THE PURPOSE OF Indian Boarding Schools was simple: “Kill the Indian, save the man.” Indigenous children were kidnapped and often sent hundreds of miles away from their homes. At the schools they were forced to assimilate; they weren’t allowed to wear traditional clothing, practice traditional religions, wear their hair in a traditional manner, or speak their native languages. They suffered physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. Disease often ran rampant in these schools, killing thousands.

For more than 100 years, the U.S. government instituted these policies of forced assimilation. And of the 300 or more schools, 73 of them were operated by the Church. No one knows exactly how many children attended boarding schools, because the government kept poor records and many children went missing. But, according to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, church institutions kept better records with a total of 239,169 children attending over the course of their operation.

“The staff at the Indian Boarding School would hit the children if they spoke anything but English, which is why my great-great-grandmother never spoke English again.”

Gaga Minnie didn’t start attending at five years old the way the government preferred. Her family hid her away and it wasn’t until she was several years older that she was discovered and taken 120 miles away to Genoa U.S. Indian Industrial School. Genoa was a federal facility and was operated like a military camp.

I don’t know a lot about Gaga Minnie’s experiences there. I know that she labored in the kitchens and became good at making bread. I know that when her mother was allowed to visit her, they shared the same bed. I know she said they were mean, that they would hit the children if they spoke anything but English. And I know that is why my great-great-grandmother never spoke English again.

Brenda Blackhawk with her Gaga Minnie.

Boarding schools caused so much lasting harm for Indigenous communities that there are entire books on the topic. As difficult as it may be to recognize that the Christian Church we love and belong to played a role in this cultural genocide, we must acknowledge it and work toward healing – healing for ourselves and the relationship we have with Indigenous communities.

In 2 Timothy 1:7, Paul writes “for God did not give us a spirit of cowardice, but rather a spirit of power and of love and of self-discipline.” It will be hard for us to confront the difficult truths of this subject, but I invite you, and church leaders everywhere, to be brave and to use the power and love and self-discipline our faith provides as we being this healing work.

We are fortunate to have an opportunity next month to learn more about the Church’s involvement in Indian Boarding Schools, and the legacy that system has left with many families. Vance Blackfox of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition will lead a joint workshop for the Minneapolis Area Synod and the Saint Paul Area Synod on April 17.